Our Pilot: Turba Farm in Beqaa, Lebanon

Adapting our Farm Model to Reality

Turba Farm was established in 2021 as a women-led, regenerative farm in Zahle, Bekaa, according to the Farms Not Arms design model. Turba — the Arabic word for soil — encompasses our values and our focus of placing soil health front and center to heal our land, our communities, and our planet.

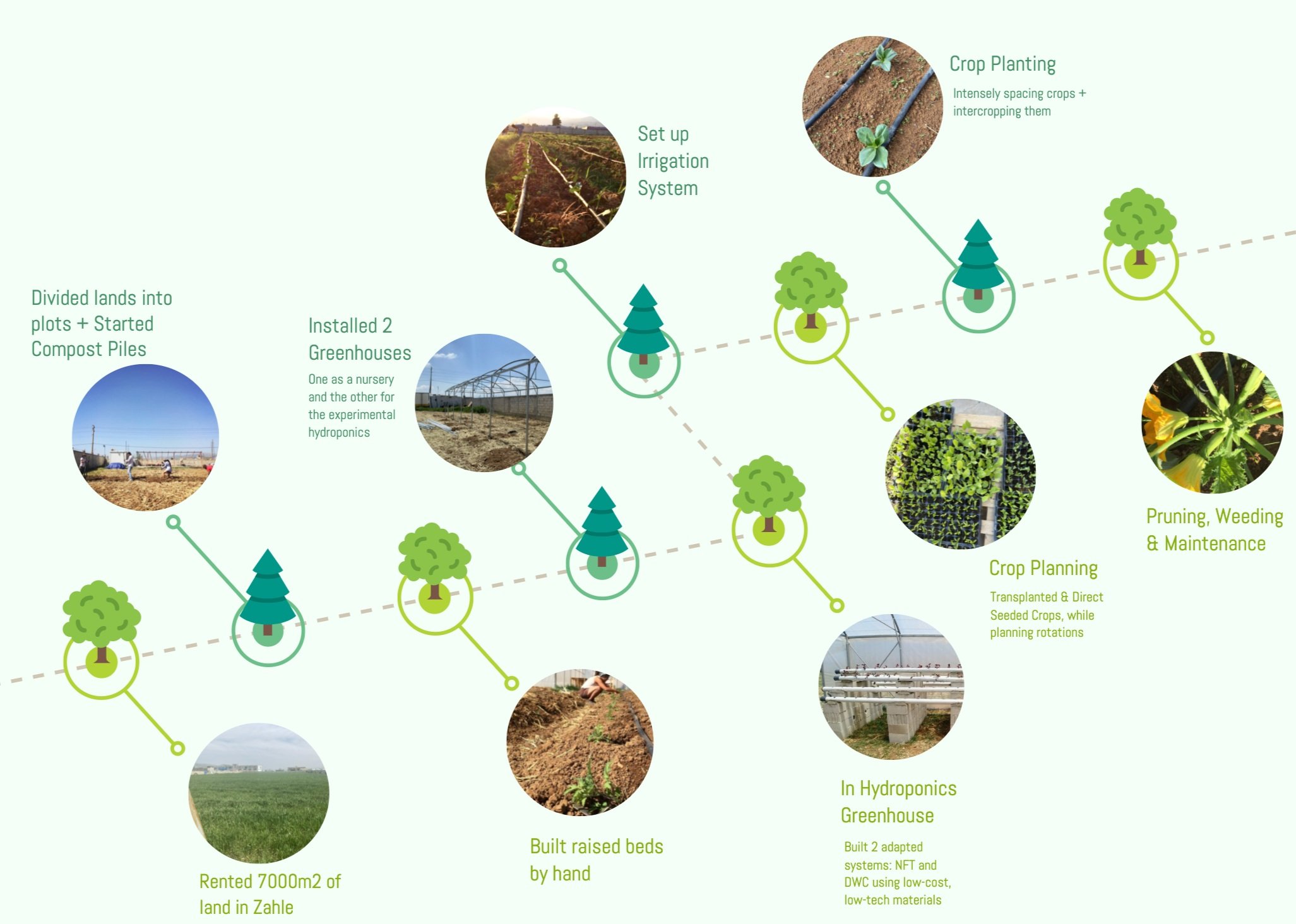

We rented an 8000m2 piece of land in Zahle that was previously covered in winter wheat, and broke ground in April 2021. We recruited a team of young farmers who are passionate about regeneration to turn the land into the farm we envision. Below are some of the steps we took in our initial farm building in 2021.

Steps to setting up the farm

Turba has been working across the value chain — from seed to product — to create healthier organic foods, heirloom seeds and grains of superior quality while restoring soil health and local ecosystems. Building towards the full-fledged version of our farm design model, we started by growing the outdoor regenerative fields and piloting a greenhouse with two different low-tech, low-cost hydroponics systems to grow leafy greens.

We’re building a multi-dimensional, holistic solution and targeting different aspects: we save and propagate native and heirloom seeds, we use regenerative agriculture principles such as crop rotation, cover crops, polycropping, densely planting, no-tilling, and more to essentially build a food forest that will slowly become a self-balancing ecosystem.

CREATING A FOOD FOREST

We’re building a multi-dimensional, holistic solution and targeting different aspects: we save and propagate native and heirloom seeds, we use regenerative agriculture principles such as crop rotation, cover crops, polycropping, densely planting, no-tilling, and more to essentially build a food forest that will slowly become a self-balancing ecosystem.

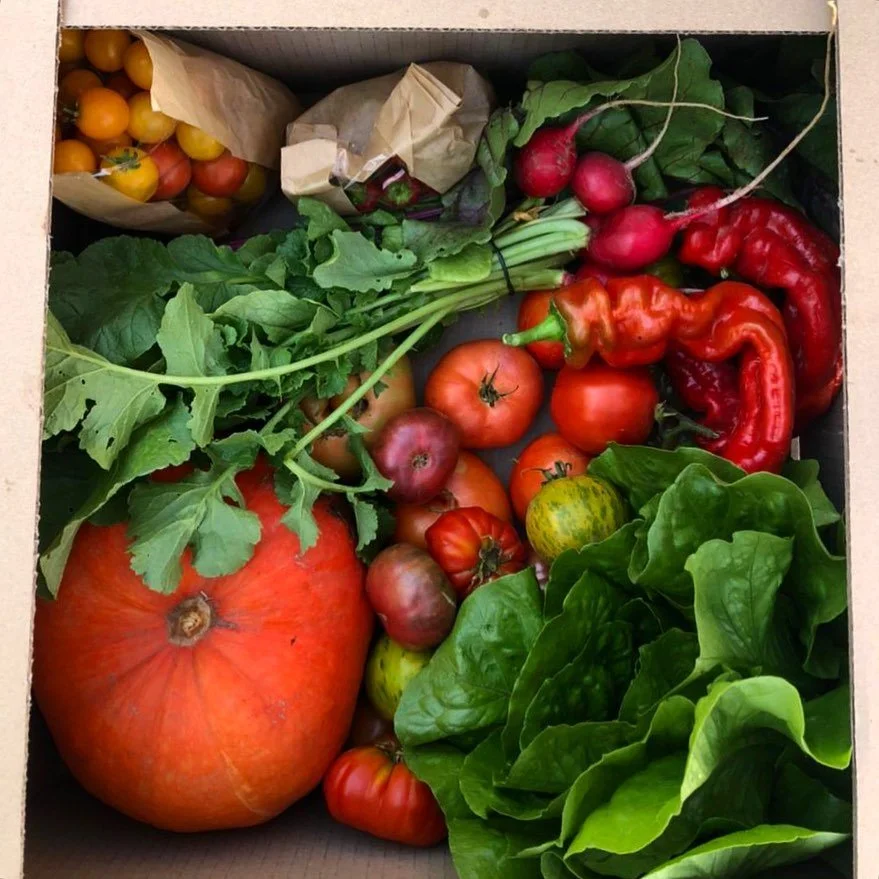

We sold weekly produce boxes that contained a seasonal selection of the organic produce harvested from the farm on any given week. Our boxes were sold directly to consumers across Lebanon.

One of our seasonal produce boxes

We also sold our produce at Lebanon’s leading farmers markets: Souk el Tayeb and Badaro markets in Beirut.

Selling at the farmers market

We donated food directly to community-based organizations in the Bekaa that were recommended to us by the Lebanese Food Bank. Soon afterwards, we started working with one of the local women cooperatives on creating our own pantry products from our produce, such as chili paste, crushed tomatoes, and organic ketchup, tomato sauce, pesto, pickles and more.

Some of the pantry products that we developed

While setting up the farm, we started building out a community of practitioners, beneficiaries, and consumers. We hired refugees and young local farmers to work alongside each other on the farm and to learn and practice regenerative agriculture — working on social cohesion through food cultivation.

During our Seed Preservation and Ancient Wheat Heritage event

In our second and third years of operation, we became founding members of the Heirloom Seed Saving Network, spearheaded by the NGO Buzurna w Juzurna. Along with a handful of organic farms in Lebanon, we worked on seed saving and preserving heirloom and native heritage seeds from Lebanon and the Levant area in the Middle East.

We are propagating them and increasing their availability, as well as producing more heirloom and native grains such as wheat and pulses such as chickpeas which are imported despite being native to Lebanon to contribute towards national self-sufficiency.

By saving heirloom seeds, particularly heirloom wheat, we’re preserving the legacy of our ancestors, supporting local agricultural traditions, and contributing to a more resilient and sustainable food system while ensuring a diverse and abundant harvest for years to come.

Harvesting heirloom wheat the traditional way

In its years of operations, Turba has been a living lab and experiment on how to optimize our regenerative farm model, both for the local climate and for our design process. It has proven to be quite successful on the agroecological and food production front: we produced over 10,000 kilograms of organic produce that were sold to market, donated, or turned into products. We’ve employed 10 full-time workers and more than 15 part-time workers at above local average wages, and impacted over 700 people directly and indirectly.

Despite that, it has been difficult to turn Turba into a self-sufficient and financially viable social enterprise, one that’s profitable and not dependent on external funding sources. Large overhead costs, skilled labor and high wages, as well as the financial crisis and general unpredictability of the country have rendered it very difficult to build a sustainable business model and operate beyond the pre-determined 3-year pilot lifespan.

Still, the model has shown that it could be financially lucrative if applied by a farmer on their land, thus foregoing some of the major costs of renting land and hiring skilled farmers.